Faith Matters: How does faith matter in our present political and cultural distress?

The Rev. Allen “Mick” Comstock at the Glacial Potholes in Shelburne Falls. STAFF PHOTO/PAUL FRANZ

| Published: 05-16-2025 9:05 AM |

I wrote this article in 2020 but it seems even more appropriate now.

How does faith matter in our present political and cultural distress?

The first answer I get to this question comes from observing how many of us church leaders and members are acting right now. It looks to me like most of us are merely taking out political opinions and decorating them with biblical or theological quotes … like our politics are shaping our faith, rather than the other way around. The country polarizes left and right and so religious people polarize right and left. I see us adding a lot of heat to the struggle but not much light.

So, my real question is: is there any way that people of faith might create light rather than just heat?

Warning: I’m asking a question I don’t already know the answer to. And, I’m writing out of my own congregational tradition in the UCC, and won’t be able to faithfully reflect other faith traditions. Which means this article is an invitation to a conversation among faith traditions about the part we might play together in discovering light.

We Congregationalists have a story about seeing light in situations of distress that, when we remember it, makes us quite proud and might help here. In the years leading up to our American Revolution, congregations and their communities were polarized between those who were faithful to the king and those who felt they must rebel. To rebel against your king was a deeply serious matter, theologically, spiritually and politically.

Before the war, in the hills of western Massachusetts, even though the churches in the valley and on the coast were still Puritan hierarchies, our churches were pretty much really Congregational democracies. The leaders of the congregations were also likely to be the leaders of the towns, so a church conversation was also a town theological conversation. Unlike the Puritans and most other denominations, Congregationalists understood their local churches to be the “Bearers of the Prophetic Office of Christ.” Others vest this office with bodies of Bishops of Presbyters, or other hierarchies beyond the local congregation.

This doesn’t mean that Congregationalists thought they were a bunch of little prophets running around their towns hollering, but that each congregation was the prophet in its community, caring for matters of justice and righteousness there, which included the theology, the spirituality and the politics of going to war against your king. Discovering the “Prophetic Word” was the work of the inspired congregation, not just inspired individuals.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

As the time for decisions drew near, in many of our towns, to the Sunday worship meetings and the Wednesday prayer meetings were added Thursday meetings for faith and politics as people tried to find their way together. The best of these were not voting meetings where a majority wins and everybody else loses. These were meetings where the congregation attempted to “become of one mind,” a practice now lost to most of our congregations except for Pastoral Search Committees. They were attempting to discover the will of God together.

Most congregations and towns didn’t end up becoming of one mind about the Revolution. They divided between Paul’s “Let every person be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except from God,” (Romans 13:1) and Peter’s “We must obey God rather than man.” (Acts 5:29)

For those congregations that genuinely struggled together to discern the will of God, these were not just proof texts but hard-won convictions derived from months if not years of studying scripture, praying, and talking together. The inevitable parting that the war finally required of them was a matter of sorrow and grief at the loss of good neighbors.

For those who didn’t do this work of discernment but merely gathered for up-down votes, the partings were cruel, with the winners bitterly casting out the losers, many of whom had to flee to Canada.

Now, with the help of this story, the question has become, for me: “Is there any way that people of faith might gather together here in these hills to struggle to become of one mind in trying to discern the will of God and thus create some light in this time of distress?”

Allen Comstock is a retired United Church of Christ pastor. He has served churches in Heath, Rowe, Stockbridge, Boston, Charlemont, and Jeffersonville, Vermont. He has been interim or bridge pastor in South Hadley, North Adams, Montague Center, Shelburne Center and and Hartland, Vermont.

Sounds Local: Shows galore planned for July 4

Sounds Local: Shows galore planned for July 4 Speaking of Nature: The most beautiful local butterfly? The Question Mark is a species of forests and forest edges

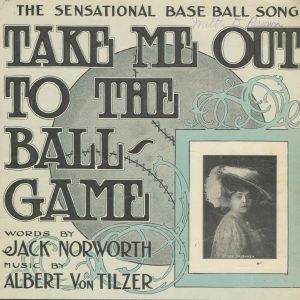

Speaking of Nature: The most beautiful local butterfly? The Question Mark is a species of forests and forest edges ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’: A crackerjack of a recipe in honor of July 4

‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game’: A crackerjack of a recipe in honor of July 4 Life’s a drag! A day in the life of producer and queen, Magnolia Masquerade

Life’s a drag! A day in the life of producer and queen, Magnolia Masquerade