Something red for Juneteenth: ‘The backbone of Juneteenth festivities has always been the table’

| Published: 06-16-2025 11:13 AM |

Thursday is June 19, also known as Juneteenth, Freedom Day, Emancipation Day, or Manumission Day.

For years, New Englanders knew little about this holiday. In 2019, when I proposed teaching a class with classic Juneteenth foods at a cooking school in Northampton, the owners said they would have to invite someone from the local historical society to give context.

(I told them not to bother. I was, and for that matter still am, the queen of historical context.)

Yankees’ unfamiliarity with Juneteenth evaporated in 2021 when the day became a federal holiday. It had long been a holiday in Texas, one of my former homes. It was celebrated informally there beginning in the 1860s and became a state holiday in 1980.

Juneteenth originated on June 19, 1865, when Union Troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, under the command of Major General Gordon Granger.

Granger announced, “The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.

“This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.”

The holiday is both solemn and joyful.

Article continues after...

Yesterday's Most Read Articles

‘A whole lot of fun’ on the water: Christmas in July boat parade returns Saturday

‘A whole lot of fun’ on the water: Christmas in July boat parade returns Saturday

New role focused on downtown development in Northfield, Turners Falls and Shelburne Falls

New role focused on downtown development in Northfield, Turners Falls and Shelburne Falls

Several area departments put out Northfield house fire

Several area departments put out Northfield house fire

Erving man, 60, found dead in Montague Plains Wildlife Management Area identified

Erving man, 60, found dead in Montague Plains Wildlife Management Area identified

Firefighters partner with Jumptown to practice water rescues in Orange

Firefighters partner with Jumptown to practice water rescues in Orange

Trio unopposed for Greenfield City Council seats

Trio unopposed for Greenfield City Council seats

It is solemn because slavery was a betrayal of human beings and of our nation’s ideals … and because the late arrival of the news of emancipation compounded the injustice of slavery.

Juneteenth arrived more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation and more than two months after the end of the Civil War.

The holiday is joyful because the federal government finally acknowledged the truth that enslaved people belonged only to themselves.

Joy was the immediate and strong reaction of Black people in Texas to their liberation.

Rowena Weatherly Keatts spoke to an oral-history interviewer at Baylor University in the 1980s. She touched on her father’s recollections of the first Juneteenth. Gus Weatherly was about 18, she recalled, at the end of the Civil War.

His daughter (and presumably he) lived in Lincolnville, Texas, a community founded by formerly enslaved people after the Civil War and named after Abraham Lincoln.

“He carried the flag in the parade that they had when they found out they were free,” said Rowena Keatts. “He said how happy they were and how they rejoiced. They were all just rejoicing about this freedom.”

According to Kelly Navies of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African-American History, Juneteenth “is a celebration of freedom, family, and the joy of being alive.”

An early term for Juneteenth was Jubilee Day. “Jubilee” is a biblical term for a celebration that was to occur every 50 years in which debts were forgiven and slaves were freed. It takes its name from the word ”yobel,” or ram’s horn.

African Americans were familiar with that horn from the biblical story of Joshua, whose followers blew rams’ horns to make the walls of Jericho tumble down. The story is retold in one of the most famous Black spirituals, “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho.”

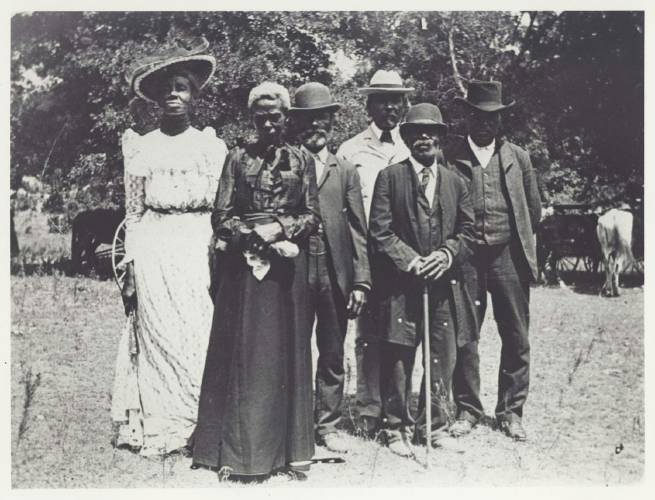

After that first day of Jubilee in 1865, African Americans in Texas put their hearts and souls into their annual celebration of Juneteenth. Vintage photographs of Black people in Texas show parades, elegant attire, and a sense of pride on this special day.

I was particularly moved by a photo of a group of residents of Austin from 1900, shared online by the Austin History Center. These older folks were probably born before the Civil War and experienced emancipation first hand. They stare confidently into the camera, wearing their finest clothes.

Juneteenth was of course an occasion for feasting. In her book “High on the Hog,” historian Jessica B. Harris wrote that “the backbone of Juneteenth festivities has always been the table. In the early years, those who had toiled in sorrow’s kitchen commemorated their liberty with some serious eating.”

Foods for Juneteenth are traditionally red. They include bright barbecue chicken, red soda or lemonade, watermelon, and red velvet cake.

These foods remind us of the blood shed by enslaved people. In addition, according to food writer Michael Twitty, for enslaved Yoruba and Kongo descendants in Texas, “the color red [was] the embodiment of spiritual power and transformation: “Enslavement narratives from Texas recall an African ancestor being lured using red flannel cloth, and many of the charms and power objects used to manipulate invisible forces required a red handkerchief.”

Fortunately for those of us around here, Juneteenth coincides with strawberry season, so cooking or baking something red is easy. The bright red of strawberries could not be more powerful or celebratory. And I defy anyone to resist their flavor when they are fresh and local here, nurtured by our long days of sunshine in June.

To celebrate Jubilee Day, I baked strawberry scones. They are easy to throw together and may be served for breakfast or tea.

I had a few extra berries so I decided to try glazing them with a little strawberry juice and confectioner’s sugar. You absolutely do not need to do this. They are lovely (and quite sweet enough) without the glaze … and a lot easier to store. Still, the pink color appealed to me.

Happy Juneteenth!

Ingredients:

for the scones:

1/2 cup sugar

2 cups flour

1 1/2 teaspoons baking power

1 teaspoon baking soda

1/2 teaspoon salt

1/2 cup (1 stick) cold sweet butter

2/3 to 1 cup chopped strawberries

1 egg

2/3 cup buttermilk

1/2 teaspoon vanilla

for the optional glaze:

a few chopped strawberries

confectioner’s sugar as needed

Instructions:

Preheat the oven to 350 degrees. Line 2 cookie sheets with parchment paper or silicone mats.

Combine the sugar, the flour, the baking powder, the baking soda, and the salt. Cut in the butter, but be careful not to overmix. Stir the berries into this mixture.

In a separate bowl, combine the egg, the buttermilk, and the vanilla. Add this mixture to the dry ingredients and blend just to moisten everything.

Quickly scoop dough (it will be moist) into rounds on the prepared cookie sheets. Small rounds will give you about 16 small scones, but you may also make 8 larger scones. Or you may aim for about 12 medium ones.

Bake for 18 to 20 minutes for small scones or a bit longer for large ones. Makes 8 to 16 scones.

If you wish to glaze some of your scones, wait until the scones have cooled completely. Pulverize strawberries using an immersion blender or mini-food processor. Stir in enough confectioner’s sugar to make a solid glaze, and drizzle it on your scones.

Tinky Weisblat is an award-winning cookbook author and singer known as the Diva of Deliciousness. Visit her website, TinkyCooks.com.

‘Everybody wants to tell their story’: Ten historical societies participating in Hilltown History Trail, Aug. 2

‘Everybody wants to tell their story’: Ten historical societies participating in Hilltown History Trail, Aug. 2 ‘Like I'm standing in a room of giants’: Meet Elana Casey, new associate director of the Augusta Savage Gallery at UMass Amherst

‘Like I'm standing in a room of giants’: Meet Elana Casey, new associate director of the Augusta Savage Gallery at UMass Amherst Valley Bounty: The joy of blueberry season: Sobieski’s River Valley Farm in Whately has been growing blueberries since 1977

Valley Bounty: The joy of blueberry season: Sobieski’s River Valley Farm in Whately has been growing blueberries since 1977 Celebrate Indigenous culture and history: 12th annual Pocumtuck Homelands Festival returns to Unity Park, Aug. 2

Celebrate Indigenous culture and history: 12th annual Pocumtuck Homelands Festival returns to Unity Park, Aug. 2